I thought it might be helpful to step back a little and take a look at the keyboard layout.

For a piano or an organ middle C, which is represented on the Treble Clef stave, by that note on the extra line below the stave;

that is the first note on this piece of music, and is in the middle of the instrument. For the AR this is the note in line with your naval on both the Keyboards. Depending on the Voices selected, this note will sound different on each keyboard, but will have the same pitch, unless you have altered that setting for the Voice selected. (You can make it one octave higher, or lower.)

The advice is then given to sit at your instrument so that the centre line of your body lines up with Middle C.

I have discovered (it wasn't difficult) that with many modern keyboards this is not the case.

Most have more notes above Middle C than below it, so to play it well you actually have to sit to one side of the centre. Because of the marvels of modern electronics, they have effectively sawn off the left hand part of the keyboard, and generated those really deep notes by some clever wizardry, so as to make the keyboard more portable.

Again this is obvious, but all the notes to the right of Middle C gradually increase in pitch, in other words they sound higher up the scale, whereas those to the left sound lower in pitch.

In music as the notes ascend the stave, they go up in pitch, and vice versa. All this helps you, as you learn to read music to appreciate that scores are logically laid out, as is your keyboard.

Now imagine if there were no black notes on your keyboard (pedalboard). You would have no idea where you were, other than by trial and error.

You will notice that the black notes occur in sets of 2 and 3 alternating as you progress along the keyboard.

All the C notes are immediately to the left of a set of 2 black notes, like this:

Before written music was invented, people copied a tune by ear. They heard it, generally sung by someone else, and then sung it to themselves committing it to memory. Surprisingly, most of us can actually still do that, though I admit some are better at it than others.

Once musical instruments were invented, it wasn't so straightforward. Because, although we can find a note with our voices fairly easily (there are a few exceptions), we do have trouble finding them on a keyboard or piano. If you try this with a recorder, flute or violin, it really becomes an even bigger challenge.

However, if someone tells you the starting note, you can make a good go of it, but it is still more difficult than simply singing it.

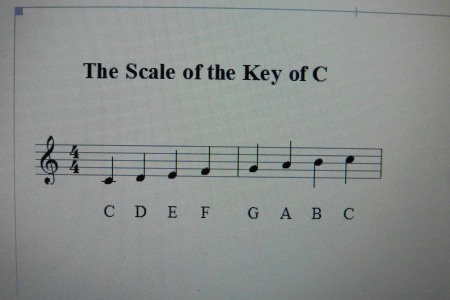

That is why, notes had to be given names, and 'they', we don't know who, chose the first 7 letters of the alphabet,

A to

G. 7 because there are only 7 different white notes available, and they repeat themselves.

You make ask the obvious question, if the alphabet begins with A, why on a keyboard do we start with C? I haven't the foggiest idea and as far as I know, neither does anyone else.

The good news is that we don't have to memorise every note on the organ. That is because once you have understood the layout of the first seven white notes, they simply repeat themselves all over the keyboards.

We explore this further in the next Reply

Peter