How to read or write time signaturesA

Bar or

measure is where the five horizontal lines of a staff are intersected vertically with another line, indicating a separation.

From now on in this Pearl we will always refer to these

measures as

bars.

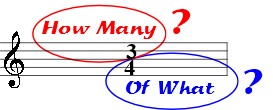

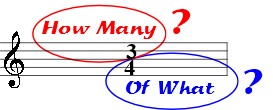

This simple graphic is useful for you to remember, when you come across any Time Signature, but it is especially helpful if it is not a familiar one to you:

Another reason for time signatures is that the

first beat in the bar is the strongest, with others, depending on the time signature, having different strengths, which are necessarily always equal to each other.

So we need to understand, how different time signatures will affect the rhythm, style, and feel of the music.

We will explain the difference in the strength of beats in the next Reply.

It is important to realize that

time signatures do not indicate the speed at which a piece of music is to be played.

The

speed is determined by

Tempo. This is either at the composer’s wish, or the discretion of the performer.

For most of us the very common Time Signatures, like 4/4

and

are about all that we can cope with, or indeed need to, as most of the scores we use are often one of these time signatures, just to get by.

Therefore, when we see 3/4 like this, we ask ourselves:

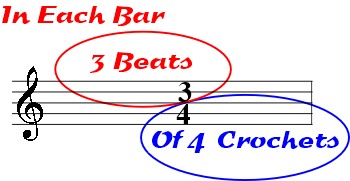

and arrive at the conclusion:

Now Time Signatures may appear rather daunting to you, but they really are that simple, although I accept they do tell us a little more than this basic fact.

As we progress in this Pearl, we’ll try to get to grips with what the

Time Signature actually means, and how we play the scores that have different sets of numbers.

In the next Reply, we examine more closely those

beats in a bar and define how their strength varies.

Peter